“Teacher educators seem to agree that, to be able to support their student teachers’ learning, they themselves should be good models of the kind of teaching they are trying to promote. However, it is clear from the literature that this congruent teaching is not self‐evident in teacher education”. (Swennen, Lunenberg, & Korthagen, 2008, p.531)

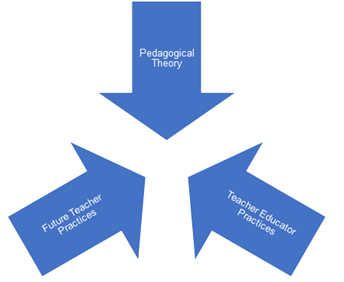

Two kinds of congruence are important in teacher education. The first is congruence between theory and practice – i.e. between what student teachers are taught and what teacher educators do on their courses. The second is congruence between modelled and target practices – i.e. between what teacher educators do and what student teachers will be expected to do in their own classrooms. Both these forms of congruence are linked (see Figure 1): as far as possible, the effective educational practices that student teachers learn about will be enacted in the work of their teacher educators who, at the same time, are providing a model of appropriate future professional practice for student teachers.

It is often the case, however, that a concern for congruence does not characterize the design of either whole pre-service teacher education programmes or individual courses within them. This can be illustrated with particular reference to assessment. On one programme I know of, student teachers study principles for effective assessment (see p2 here for an example of a useful checklist for assessment in HE) but the manner in which assessment takes place often seems to be at odds with such principles. So, while, for example, they learn about the importance to assessment of clear objectives, reliability, validity and feedback:

- student teachers receive limited prior information about assessment formats (such as the nature of a forthcoming examination)

- it is unclear to student teachers what they need to study prior to an examination (scope of the assessment)

- student teachers are assessed against skills they have not been given opportunities to develop

- content not focused on during a course appears in an examination

- the scope of the content to be assessed is unfeasibly broad

- assessment emphasizes the recall of facts

- assessment rubrics are vague

- student teachers receive no or limited written feedback to explain assessment outcomes

- multiple pieces of work contribute to a final score but the breakdown of marks in the result is not explained

- assessment criteria are not pre–defined or referenced when results are communicated

- assessment is entirely summative

- different teacher educators (even those co-teaching a course) assess in very different ways.

Collectively, such practices create strong tensions among the theory of assessment that student teachers are taught, what teacher educators do, and the assessment practices future teachers are expected to adopt. These tensions can have a negative impact on student teachers; for example, they may come to believe that what they study on their programme and what happens in actual educational practice are not connected. It is thus important to minimise such tensions (not only in relation to assessment but also for teaching and learning more generally) and this can be achieved through a process of reflection and alignment in which teacher educators ask themselves (and – given the value of collaborative reflection (pdf download) – ideally one another) questions such as these:

- what educational principles regarding teaching, learning and assessment are the student teachers studying (on this programme or course)?

- to what extent are my teaching and assessment practices as a teacher educator aligned with such principles?

- what factors might explain any lack of alignment?

- what changes in my approach would strengthen the congruence between what the student teachers are taught, what I do, and what we would like them to do as future teachers?